Erik Satie (1866-1925) was a French composer and pianist. At the age of 13 his stepmother, a pianist and composer herself, enrolled the young Satie in the Paris Conservatoire. Satie strongly disliked the institution, which he described as “a vast, very uncomfortable, and rather ugly building; a sort of district prison with no beauty on the inside, nor on the outside, for that matter”.

There he studied with Emile Decombes who had been a pupil of Frederic Chopin. In 1880, after taking his first examinations as a pianist he was described as “gifted but indolent”. The following year Decombes called him “the laziest student in the Conservatoire” and in 1882 at the age of 16 he was expelled from the Conservatoire for his unsatisfactory performance.

Three years later in 1885, he was readmitted to the Conservatoire, this time in the intermediate piano class of his stepmother’s former teacher Georges Mathias. His second stint at the school was no better than his first. He made little if any progress. Mathias described his playing as “insignificant and laborious” and Satie himself as “Worthless, three months just to learn the piece and he still cannot sight read properly.”

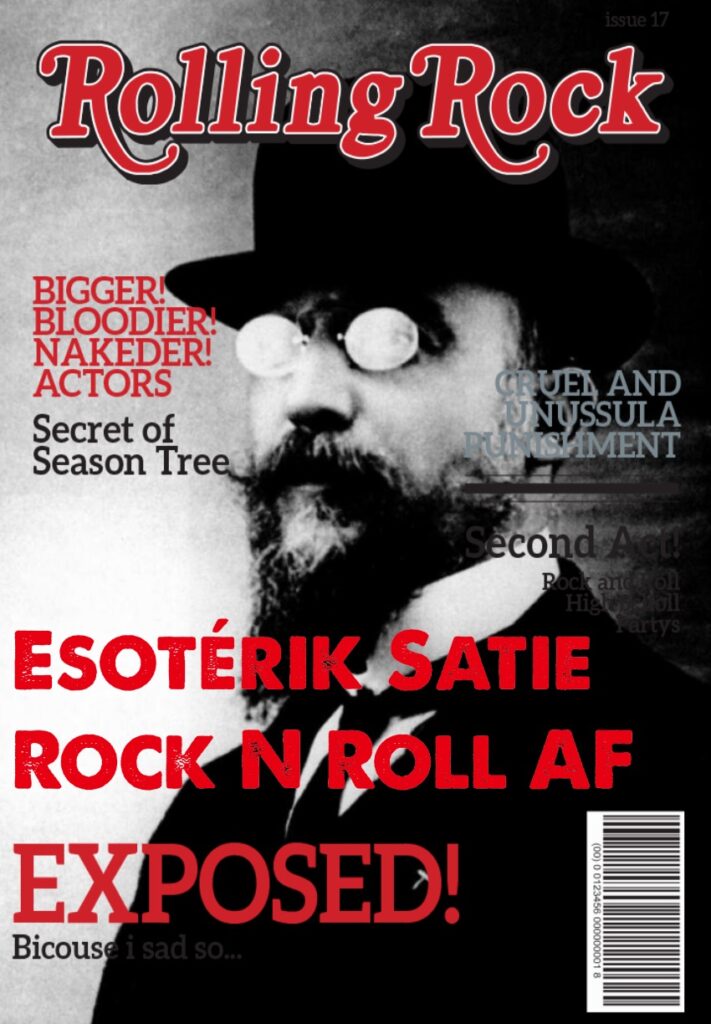

It was at this time that Satie began to spend much of his time at the Notre-Dame de Paris contemplating the intricate stained glass windows and in the National Library examining obscure medieval manuscripts. His obsessive interest in both these places led a friend to later dub him “Esotérik Satie”.

Keen to leave the Conservatoire, Satie volunteered for military service at the age of 21. He found army life no more to his liking than the Conservatoire, and deliberately contracted an acute case of bronchitis by standing bare chested outside in the open on a particularly cold winter night. After three months’ convalescence, he was invalided out of the army.

Now 22, Satie moved back to Paris living close to the popular Dadaist cabaret Chat Noir where he became an habitué and later resident pianist. The Chat Noir was known as the “temple de la ‘convention farfelue’” (the temple of zany convention). Satie’s biographer would say of this period, “Free from his restrictive upbringing, Satie enthusiastically embraced the reckless bohemian lifestyle and created for himself a new persona as a long-haired man-about-town in frock coat and top hat”. This was the first of several personas that Satie would adopt over the years.

He earned a modest living as a pianist and conductor at the Chat Noir, before falling out with the proprietor, moving to become second pianist at the nearby Auberge du Clou. There he became a close friend of Claude Debussy who proved a kindred spirit in his experimental approach to composition. Both were bohemians, enjoying café society and struggling to survive financially.

Frequently short of money, Satie moved from his lodgings in the 9th arrondissement to a small room in the rue Cortot so high up the Butte Montmartre that he said he could see all the way to the Belgian border from his apartment window.

It was at this time that Satie, just 26 years of age, openly challenged the musical establishment, proposing himself, albeit unsuccessfully, for a seat at the Academie des Beaux-Arts made vacant by a death in 1892.

Between 1893 and 1895, Satie, wearing quasi-priestly dress, was the founder and only member of Église Métropolitaine d’Art de Jésus Conducteur (Metropolitan Church of Art of Jesus the Conductor). From his “Abbatiale” in the rue Cortot, he published scathing attacks on his artistic enemies.

In 1893 Satie had what is believed to be his only love affair, a five-month liaison with the 28 year old painter Suzanne Valadon. After their first night together, he proposed marriage. They did not marry, but Valadon moved to a room next to Satie’s at the rue Cortot. Satie became obsessed with her, calling her his Biqui and writing impassioned notes about “her whole being, lovely eyes, gentle hands, and tiny feet”.

During their relationship Satie composed the Danses gothiques as a means of calming his mind, and Valadon painted his portrait, which she gave him. After five months she moved away, leaving him devastated. He said later that he was left with “nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness”.

At the age 29 in 1895, Satie changed his image once again, this time to that of “the Velvet Gentleman”. From the proceeds of a small legacy, he bought seven identical dun coloured velvet suits. His biographer noted this change “marked the end of his Rose+Croix period and the start of a long search for a new artistic direction”.

32 years old and in search of somewhere cheaper and quieter to live, Satie moved in 1898 to a room in the southern suburbs, in the commune of Arcueil-Cachan, eight kilometres (five miles) from the centre of Paris. This remained his home for the rest of his life. No visitors were ever admitted.

Soon after moving he joined the Socialist Party, later switching to the Communist Party after its foundation in 1920. In spite of his political affiliations, Satie adopted a thoroughly bourgeois image. His biographer noted “With his umbrella and bowler hat, he resembled a quiet school teacher. Although a Bohemian, he looked very dignified, almost ceremonious”.

Satie earned a living as a cabaret pianist, adapting more than a hundred compositions of popular music for piano or piano and voice, eventually adding some of his own. Between 1898 and 1908, he composed and arranged the music for around thirty Hyspa texts. These songs, which caricatured current political events, enabled Satie to explore the use of musical quotations for humorous purposes that would characterize his later work. Satie would eventually reject all his cabaret music as vile and against his nature. Only a few compositions that he took seriously remain from this period. Few were presented, and none published at the time.

A decisive change in Satie’s musical outlook came after he heard the premiere of Debussy’s opera Pelleas et Melisande in 1892. He found it “absolutely astounding”, causing him to re-evaluated his own music. In a determined attempt to improve his technique, and against Debussy’s advice, Satie went back to school at age 40, enrolling as a mature student at Paris’s second main music academy, the Schola Cantorum.

In 1911, in his mid-forties, Satie’s work finally came to be noticed by the general public. Maurice Ravel began playing some of Satie’s early works in concert. Suddenly Satie was seen as “the precursor and apostle of the musical revolution now taking place” and, as such, became a focus for young composers of the day. Debussy, having orchestrated the first and third solo piano Gymnopédies Satie had written as a teenager, conducted both in concert. Soon after music publisher Demets asked Satie for new works, enabling Satie to finally give up his cabaret work in order to devote himself full time to composition.

At this time the press began to write about Satie’s music. The leading pianist of the era, Ricardo Vines, began giving celebrated first performances of many of Satie’s works. The newly famous Satie became the focus of successive groups of young composers, who he first encouraged and then distanced himself from, sometimes rancorously, when their popularity threatened to eclipse his or they otherwise displeased him. He even quarrelled with his old friend Debussy as late as 1917, resentful of the latter’s failure to appreciate his recent compositions. The rupture lasted for the remaining months of Debussy’s life, and when he died of cancer the following year at the age of 55, Satie refused to attend his funeral.

The First World War restricted concert giving to some extent, but Satie’s biographer noted that the war years brought “Satie’s second lucky break”, when Jean Cocteau heard Viñes and Satie perform the Trois morceaux in 1916. This led to the commissioning of Satie’s ballet Parade which premiered in 1917 with music by Satie, and sets, costumes by Pablo Picasso. The work was the Succès de scandale (“success from scandal”) of the day with its jazz rhythms and unusual instrumentation including parts written for typewriter, steamship whistle and siren. Parade firmly established Satie’s name before the public, after which his career centred permanently on the theatre, writing mainly to commission.

In October 1916, Satie received a commission from the Princesse de Polignac. The Princess, born in Yonkers, New York in 1865 as Winnaretta Singer, was the twentieth of the 24 children of Isaac Singer, founder of what became one of the first American multi-national businesses, the Singer Sewing Machine Company. The American-born heiress to the Singer sewing machine empire used her fortune to fund a wide range of causes, notably a musical salon where her protégés included Debussy and Ravel as well as numerous public health projects in Paris, where she lived most of her life. She entered into two marriages that were reportedly unconsummated, openly enjoying many high-profile relationships with women. She was styled as Countess Louis de Scey-Montbéliardduring her first marriage and as Princess Edmond de Polignac following her second marriage in 1893 at the age of 28.

Ultimately the Princess funded what Satie’s biographer considers the composer’s masterpiece, the symphonic drama Socrate (1917–1918). The chamber oratorio consists of excerpts from Plato’s Socratic dialogues from Victor Cousin’s lyrical translations from 1822 through to 1840.

Composition for Satie’s Socrate was interrupted in 1917 by music critic Jean Poueigh’s libel suit and the threat of a jail term for Satie. At the time Poueigh was writing reviews for the Ère nouvelle. After attending a performance of Satie’s ballet Parade he wrote a virulent criticism. Satie responded by sending the critic incendiary letters, the most famous of which began, “Monsieur and dear friend, you are only an arse, worse, an arse without music”. The correspondence was sent on a postcard which would have been easily read by anyone, not the least of which being the critic’s colleagues at the publication where he worked. Satie fell short of a one-year sentence for public defamation. During the scandalous trial Jean Cocteau was arrested and beaten by police for repeatedly yelling “arse” in the courtroom. Ultimately Satie was given a sentence of eight days in jail and forced to pay a fine. On appeal his prison sentence was suspended and ultimately vacated.

With his legal battles behind him, Satie resumed work on his symphonic Socrate oratorio which he himself described as “a return to classical simplicity with a modern sensibility”. Igor Stravinsky, who Satie deeply admired, praised the work.

In his later years Satie was in demand as a journalist, making contributions to the Revue musicale, Action, L’Esprit nouveau, the Paris-Journal and other publications from the Dadaist 391 to English-language magazines Vanity Fair and The Transatlantic Review. As he contributed anonymously and often under pen names it is not certain how many titles he wrote for though some have suggested as many as 25.

Satie’s 1924 “ballet obscène”, Relâche (“Cancelled”), provoked headlines with its opening night scandals. The title of the ballet is a Dadaist joke, as relâche is the French word used on posters to indicate that a show has been canceled or the theater has been closed. The first performance was indeed canceled, due to the illness of the principal dancer.

Filmmaker Rene Clair created a cinematic entr’acte to be shown during the ballet’s intermission. The film, simply titled Entr’acte, consists of a scene shown before the ballet and a longer piece between the acts. The nonsensical film features Satie and other well-known artists as actors.

The music Satie composed for the ballet latter is a comedic bricolage (French for DIY “do-it-yourself projects”, a work from a diverse range of things that happen to be available, or work constructed using mixed media). Satie juxtaposed high art with popular music from the cabaret to create his mischievous music “cancellations” as he referred to them.

One critic called it “a miserable pastiche”. Satie christened it “obscène”, going so far as to call it “pornographic”. In the original concert program for the premiere Satie wrote:

“The music for Relâche? I was portraying people “out on a spree”. Using popular themes for the purpose. These themes were powerfully “evocative”. “Faint-hearts” and other “moralists” will reproach me for making use of these. There is only one judge I defer to: the public. It will recognize these themes and will not be shocked in the least to hear them. Aren’t they “human”, after all? Let anyone who dreads such “evocations” retire.”

Despite being a musical iconoclast, and encourager of modernism, Satie was uninterested to the point of antipathy in innovations such as the telephone, the gramophone and the radio. He made no recordings, and as far as is known heard only one single radio broadcast (of Milhaud’s music) and made only one telephone call.

Although his personal appearance was immaculate, his room at Arcueil, according to his biographer, was “squalid”. After Satie’s death, scores to several of his important works, long believed lost, were discovered amongst the trash that he had accumulated in his tiny one room apartment. He was completely incompetent with anything to do with money. Having depended considerably on the generosity of friends in his early years, he was little better late in life after he began to earn a good income from his compositions. He either spent it or gave it away as soon as he earned it. He liked children, and they liked him, but his relations with adults were seldom straightforward. One of his final collaborators said of him:

Satie’s case is extraordinary. He’s a mischievous and cunning old artist. At least, that’s how he thinks of himself. Myself, I think the opposite! He’s a very susceptible man, arrogant, a real sad child, but one who is sometimes made optimistic by alcohol. But he’s a good friend, and I like him a lot.

Satie never married. His home for most of his adult life was a single small room. He adopted various images over the years, including a period in quasi-priestly dress and another in which he always wore identical velvet suits. He is perhaps best remembered for his last persona, smartly dressed in a neat bourgeois suit complete with tiny spectacles, bowler hat, wing collar and umbrella.

Throughout his adult life Satie was a heavy drinker and in 1925 his health collapsed. He was taken to the Hôpital Saint-Joseph in Paris where he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver. Quite literally, he drank himself to death, dying in hospital at 8:00 p.m., July 1, 1925. He was 59. He is buried at the cemetery in Arcueil, Paris.